Excavating women’s history from the archives

Alison Hewitt I UCLA

UCLA doctoral candidate Jessica Sherrill is teaching her students about female representation in STEM

Science and literature normally reside at opposite ends of the academic spectrum, but when UCLA student Jessica Sherrill expanded her undergraduate physiological science major to double-major in English, she discovered intriguing overlaps in the histories of the two disciplines.

“I had already learned about important Victorian discoveries from a scientific standpoint, but studying literature provided a missing piece of the picture,” Sherrill said. “English illuminated the full intellectual context of who knew whom, what social circles scientists moved in, and which other writers and thinkers they had access to. For example, Michael Faraday, whose incredible discoveries are the foundation of modern physics, chemistry and engineering, was close friends with novelist Charles Dickens.”

Now about to earn her Ph.D. in English, Sherrill studies and teaches the literary history of computing, artificial intelligence and secret codes in Victorian England. Her courses explore overlooked and untraced STEM narratives that celebrate the contributions of women and other marginalized figures who deserve greater recognition.

In the class Sherrill recently taught on literary computing from Chaucer to ChatGPT, students learned about Ada Lovelace, the Victorian countess and computer pioneer now recognized for writing the first computer algorithm. Lovelace, the daughter of Romantic poet Lord Byron, was allowed to include her theories in just one published work. Even then, her writing appeared only as footnotes.

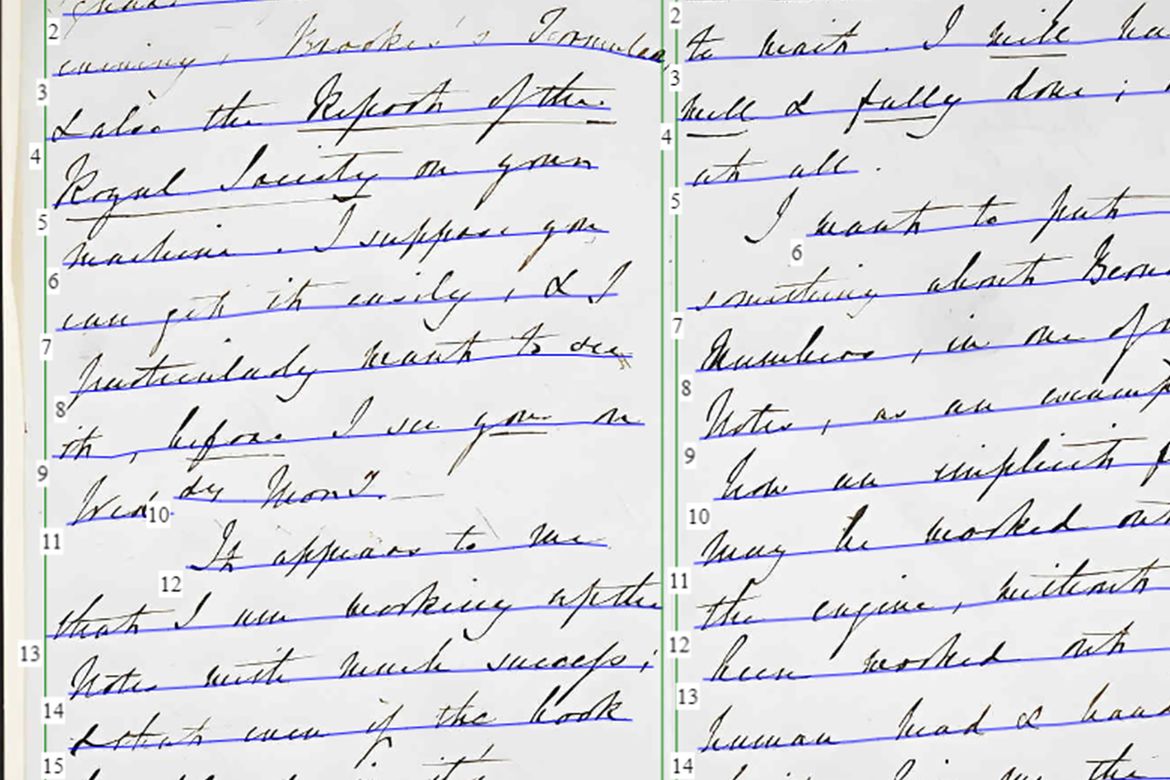

Sherrill observes how, despite Lovelace becoming “a marginal figure on the text’s literal periphery,” her footnotes contain the detailed computer algorithm for which she is now celebrated. Published in 1843, when Lovelace was 27, her footnotes include the first modern computing theories about using artificial-intelligence technology to create artistic work, like musical scores. But her archived private correspondence shows much broader contributions to the scientific conversation of the 1830s and ‘40s.

Read the full story.

Photo caption: Students in Jessica Sherrill’s class are using Transkribus to analyze handwriting by 19th century computer pioneer Ada Lovelace.

Photo credit: Alison Hewitt/UCLA